Emotional Marketing: The Evolution of Sanitary Pads Ads

This blog examines the history of the sanitary pad ads, one of the most profound cultural changes in the last century, proving that marketing strategists have a significant influence on the progress of many social movements.

It has been over two years since the #MeToo campaign made the bro culture problem of Silicon Valley become a problem. From Bumble’s “The Ball Is in Her Court”, to Microsoft’s “We All Win”, feminism has also gone viral in marketing campaigns. Why “femvertising” has become a popular branding tool? Besides the call for cultural change, arguably a more important driver is the tool we rely on to convince consumers to purchase the goods or services we are marketing – emotion.

Ethically I should be very careful about today's topic - emotion marketing, and as a business, you need to be more so.

Taking small steps, I will review the history of the sanitary pad ads, one of the most profound cultural changes in the last century, to show how marketing strategists can influence the progress of many social movements.

1920s - 1970s: Shame

The early sanitary pads companies demonstrated the true art of persuasion in marketing – making women believe that they should feel some sense of guilt if they miss the advertising opportunity presented. Starting from the 1920s, depictions of periods in sanitary pads ads have ranged from wildly inaccurate to being the subject of jokes and derision.

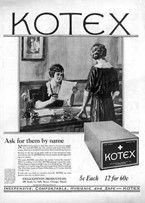

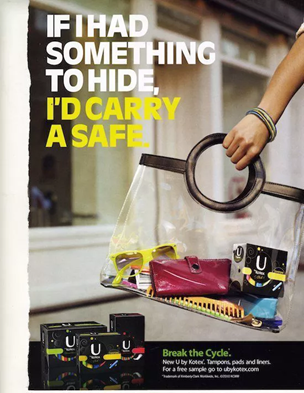

In the 1920s, Kotex marketed the first disposable sanitary pad with the messaging of "easy to conceal and carry". Through its advertising campaigns, Kotex reinforced that menstruation was a shame problem, rather than a natural hormonal process that a woman's body goes through each month.

Until the 1980s, all sanitary pad ads had been bonded with shame with 4 noticeable features about their ads:

1) There is no product description on the packaging.

For instance, "There is nothing on the blue Kotex package except the name," the ad reads. “Ask for them by the name” implies that women should only buy the pads without notice. Menstruation remained a taboo topic, which contributed to a cent’s long culture of silence and misinformation around hygienic practices.

2) Menstrual symptoms are labeled as "disease”.

From abdominal cramps to mood swings, common normal physical symptoms of menstruation were marketing hotspots. Companies pictured sanitary pads as "doctors" helping women relieve pain or “social embarrassment”. Such messaging became very disturbing to manipulate women’s anxiety about the menstrual period as drivers for business revenue. For example, the deodorant advertisement in the late 60s emphasized that body odor during the menstrual period is a “noticeable” and “shameful” problem

3) Sanitary pad ads were associated with "miracle experience".

With the stereotype that sports like horse riding, surfing, or swimming were challenging for women, sanitary pads were depicted as so “magical” that women could do all kinds of things that they could not normally do without wearing them. There was a joke at the time: a child only had one dollar, and his friend persuaded him to buy a cotton sliver so that they could go swimming, horse racing, and even skiing.

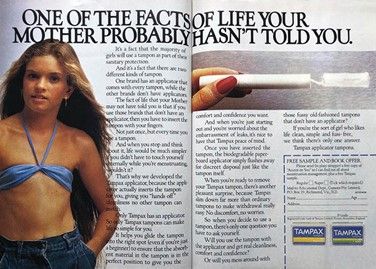

4) Over-sexualized images of young women were used to sell period products.

Over-sexualization could cause society to view women as “less capable and less intelligent”. Such imagery used widely in women's products marketing set unrealistic expectations on how a menstruating girl should look and feel.

For decades, sanitary pad ads focused on that people should be discreet about their menstruation like it’s something to be ashamed of; but paying no attention to women's real needs. Shame became a powerful marketing tool rather than empowering female consumers.

1980s-2000s: Awakening

The sanitary pad ads had tapped into women’s insecurities about family and sexuality for 50 years until the feminism movement in the early 80s made women awaken from their menstruation shame.

Feminism in the US started as early as 1960 but first-wave feminism mainly focused on overturning legal obstacles such as women’s voting and property rights. It was the second wave starting in the 80s that broadened the debate to issues including sexuality, family, the workplace, and reproductive rights, which also made significant changes to sanitary pad marketing messages.

In an ad by Tampax in 1985, the word “period” was uttered for the first time on TV.

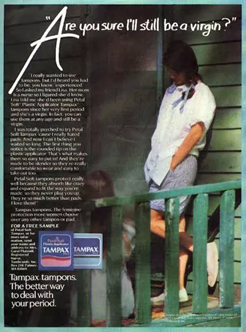

Five years later, Tampax broke the rumor at the time that the person who used the tampon was not a virgin. It clarified, "In fact, you can use it at any age, and you are still a virgin." Sanitary pads began to be more widely promoted and women's interests became the marketing points.

However, the shame associated with menstruation remained.

For instance, reinforcing the idea that period blood is too gross to show on TV, the weird clinical blue liquid used in menstrual pad ads dominated TV screens throughout the 90s. In 2005, a Tampax ad focused on two pupils caught passing a tampon in class. However, the girl didn’t want her class to know about her period. Thanks to the discreet Tampax packaging, she succeeded in fooling the teacher and getting away with their secret transaction.

It’s baffling, to say the least, that in the 2020 period brands still face backlash for ’daring’ to open up the conversation surrounding menstruation.

2010s - 2020s: Challenging the Shame

Since the 2010s, the sanitary pad ads have made unprecedented progress, with more brands breaking the shame and advocating for women’s real needs. But to reach a "reasonable" acceptance of menstruation is an ongoing struggle.

In 2012, a consumer posted a complaint about Bodyform’s ads being deceptive because menstruation is not as good as the ads describe. Then Bodyform replied wittily through a video, acknowledging that the images are lies and there is no "happy period". "We do these advertisements to protect men from the cruel reality of women." Facing the challengesofm male audience, Bodyform's reply tore through the "menstrual shame" and became a revolutionary step in sanitary pads advertising.

In 2014, HelloFlo launched an ad about the "First Moon Party", in which a little girl uses red nail polish to cheat her mother to have menstruation, and her mother held a grand party for her daughter to commemorate her first time. Although it was painted with red nail polish, it was the first time that the image of a red sanitary napkin appeared in an advertisement.

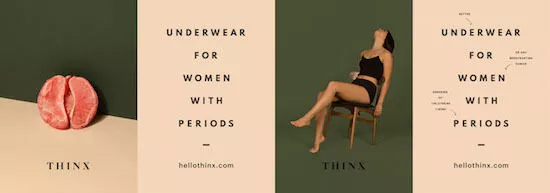

By 2015, the advertisements about menstruation were more artistic, but it was still difficult to escape the fate of being banned. For example, a print advertisement for the Thinx was banned from the New York City subway because of the word "period" in the advertisement and “suggestive” imagery, such as grapefruit and runny eggs to allude to the female anatomy.

Then, the founder of the Thinx brand raised objections, and amid many protests, the advertisement was eventually approved and went up in three subway stations throughout New York City, including bustling Grand Central and Williamsburg’s Bedford Avenue stop.

In 2017, the "Blood Normal" campaign went viral around the world. Bodyform proposed to replace the blue liquid in previous advertisements with red blood. However, this initiative encountered a lot of opposition. In 2019, LLibresse's(Bodyform's Asian brand) "Blood Normal" commercial in the Australian market received more than 600 complaints, becoming the most complained one that year. advertising.

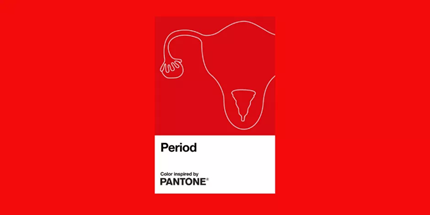

In 2020, the Pantone Color Institute announced a new color “Period red”, which is the color of menstruation, to smash the taboos and get people talking about menstruation. The new hue -- an "energizing and dynamic red shade that encourages period positivity," according to a press release -- was launched as part of the Seen+Heard campaign, an initiative by Swedish feminine care brand, Intimina. Vice president of the Pantone Color Institute, Laurie Pressman, described the color as a "confident red" that can help encourage positive conversations about menstruation.

***

I remembered a quote from Marianne Cooper, a sociologist at Stanford University:

“Changing culture is all about these kinds of micro-moments. It is the micro moments that will become the macro and change the norms of professionalism.”

From television to social media to the outdoors, the space for women's product advertising is becoming wider, and I am grateful for those who have led the journey with significant micro-moments" so far. However, we still need more “micro moments”. Until today, menstruation remains a taboo topic in many parts of the world, impacting women’s health and socioeconomic status.

Whatever industry you are working in, if your marketing message leverages emotions, it is important to understand where the line is.